- Casey Neistat in "Filmmaking is a Sport" bit.ly/3d2pwo4 (Context starts @1:33; phrase @1:49)

Over the last few years, perhaps triggered by the pandemic, there has been an uptake of people wanting to join the learning/training industry. Teachers are looking to transition from teaching children to training adults and folks from other related industries such as media and User Interface Design are looking to explore how best to make their way into the field of learning experience design. And to address this growing need, there are articles, posts, videos, and a range of individuals and consulting firms that are sharing their version of the steps to become an instructional designer.

Some wonderful people from the L&D industry have provided specific tips and strategies to build a career in the field of instructional design. Some of those resources provide a fairly decent picture of what it takes to become an instructional designer. There is a good focus on the skill set including technical and technological skills and there is also a lot of discussion around the glamour behind the job - good salary, fancy titles, flexible work arrangements, awards and recognition, career progression, etc.

However, the one thing that I find missing in many of those articles, blog posts, videos, and webinars is the gap between describing what expertise looks like versus describing what it takes to develop it.

Few people talk about the 'rougher' side of how to become an instructional designer and how it takes solid, grinding work to get to the glamorous part. Yes, there are opportunities to be creative, but there can also be endless days of monotonous work. Yes, there are a variety of projects but there can also be years of doing the same thing for the same client or doing the same thing for different clients. Yes, there are rewards but there can also be mistakes with serious consequences.

So, what is this process of developing expertise and why is it not glamorous?

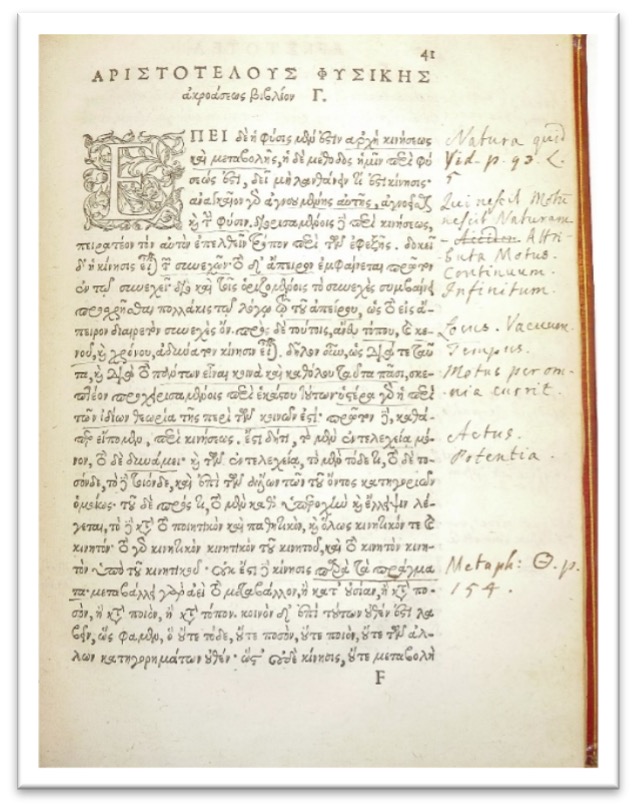

Developing expertise is not simple and there is no mess-free way to do it. No two people develop expertise in the same way and the struggle is real. One cannot become an Instructional Designer only by gathering certificates, attending conferences and webinars, learning software tools, and collecting other 'shiny' stuff. It is the everyday, so-called, boring things that Instructional Designers do - like stakeholder communication, project planning, content research, needs, task, audience, and content analysis, instructional writing, etc. that yield the results. The routine stuff in an Instructional Designer's job can sometimes be predictable and monotonous. But it is important to do the so-called boring stuff and keep doing it well over a long period in order to become successful. It is the days, weeks and years of doing basic things right - every time - that have a compounding effect on developing expertise. But it takes more than experience; it also needs time and continuous feedback.

Author of New York Times bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman says, "True intuitive expertise is learned from prolonged experience with good feedback on mistakes."

Patty Shank describes in this article how, "Expertise takes sustained, deliberate practice in the tasks of expertise over time."

Mary Myatt describes in her article, "If everything is easy, it is hard for learning to take place. Expertise comes through the struggle of not knowing everything, having sufficient support and making sense of it on our own terms"

While the 10,000-hour rule on developing expertise widely promoted in popular literature has been dismissed and debunked, there is something to be said about the value of and importance of the grind.

The grind is not glamorous but without it, there is no glamour.

https://youtu.be/ksopQLMQsq8 - Daniel Kahneman

https://www.td.org/insights/science-of-learning-101-job-performance-and-expertise - Patty Shank

https://www.marymyatt.com/blog/developing-expertise - Mary Myatt